Brief History of Guam

The island of Guam is the farthest Western land mass of the United States. Located in the North Western Pacific Ocean, approximately 3,945 miles West of Hawaii, 1,541 miles East of the Philippines, 1,624 miles South of Japan, and 2,765 miles North of Australia, Guam is an important commercial gateway to Asia and the Pacific. Guam is also important as a strategic communications hub and forward defense outpost for the Pacific and Asia. This site provides a basic outline of Guam’s unique history and culture derived from its original native inhabitants, the Chamorro who were on Guam as early as 2,000 B.C. The proud Chamorro culture has survived and flourished to the present day. Today, Guam culture has been influences by enriched over the centuries by the countless Pacific Islanders, Europeans, Asian, Mexican and North American peoples who have visited, occupied, and immigrated to Guam. Today, Guam is truly cosmopolitan community.

Ancient Guam – The Chamorro

The original inhabitants of Guam are believed to have been of Indo-Malaya descent originating from Southeast Asia as early as 2,000 B.C., and having linguistic and cultural similarities to Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. The Chamorro flourished as an advanced fishing, horticultural, and hunting society. They were expert seamen and skilled craftsmen familiar with intricate weaving and detailed pottery making who built unique houses and canoes suited to this region of the world. The Chamorro possessed a strong matriarchal society and it was through the power and prestige of the women, and the failure of the Spanish overlords to recognize this fact, that much of the Chamorro culture, including the language, music, dance, and traditions have survived to this day

The Latte Stone – Guam Icon

The Latte Stone – Guam Icon

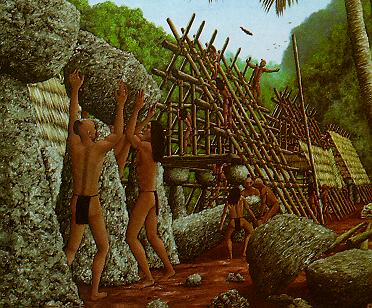

Latte Stones are the stone pillars of ancient Chamorro houses. Found nowhere else in the world, the Latte Stone has become a symbol and the signature of Guam and the Marianas Islands. Original Latte Stones were comprised of two pieces, a supporting column (halagi), made from coral limestone topped with a capstone (tasa), made from coral heads, which were usually carried several miles from the quarry site or reef to the location of the house. Customarily, bones of the ancient Chamorro’s, their possessions, such as jewelry or canoes, were buried below the stones.

Archaeological milestones of ancient Guam are tied to the Latte Stones: Transitional Pre-Latte (AD 1 to AD 1000), the larger Latte Period (AD 1000 to AD 1521), and Early Historic Period (AD 1521 to 1700). Today, many latte sites can be found in Northern Guam. Replicas and images of Latte Stones are common in carvings, jewelry, on t-shirts and hats and in logos. Latte Stones are respected and are untouched. A human interloper at Latte sites may encounter Taotaomona (ancestral Chamorro spirits). Eight ancient latte stones transferred from their original location in Me’pu in Guam’s Southern interior are on display in Latte Stone Park in Hagatna.

The Spanish Era (1565 – 1898)

The Spanish Era on Guam lasted for over 333 years from 1565 through 1898. The first known contact between Guam and West occurred when Ferdinand Magellan anchored his small 3-ship fleet in Umatac Bay on March 6, 1521. Hungry and weakened from their long voyage, the crew hastily prepared to go ashore and restore provisions. The excited native Chamorro’s, who did not share the Spaniards concept of ownership, canoed out first and began helping themselves to everything that was not nailed down, leading the Spaniards to label Guam “The Island of Thieves”. The weakened sailors had trouble fending off the tall and robust natives until a few shots from the Trinidad’s big guns frightened them off the ship and they retreated into the surrounding jungle. Magellan was eventually able to obtain rations and offered iron, a commodity highly prized by Neolithic peoples, in exchange for fresh fruits, vegetables and water. Details of Magellan’s visit and the first known Western documentation of Guam and the Chamorro people may be found in the journal of Antonio Pigafetta. Pigafetta was Magellan’s chronicler and one of only 18 original crew members to survive Ferdinand Magellan’s ill-fated circumnavigation of the globe.

Guam and the other Mariana Islands were formally claimed by the Spanish Crown in 1565 by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi. In 1668, Jesuit missionaries led by Padre Diego Luis de San Vitores, arrived on Guam to establish their brand of European civilization, Christianity and trade. The Spanish taught the Chamorro’s to cultivate maize (corn), raise introduced cattle and tan hides, as well as to adopt western-style clothing. Because of it’s strategic mid-Pacific location, Guam became a regular port-of-call for the Spanish treasure galleons that crisscrossed the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and the Philippines. After being ceded to the United Stated by Spain in 1898, Guam remained a strategic refueling and replenishment base for American Navy and commercial vessels between the United States and America’s new colonies in the Far East. The Spanish established their capitol in Hagatna and constructed a Governor’s Palace in 1736. Most of the palace was destroyed during shelling of Hagatna in World War II. The courtyard, the Plaza de Espana, survived and is a popular visitor attraction today.

Influence of the Catholic Church

Once Christianity was firmly established by the Jesuits in 1898, the Catholic Church became the focal point for village activities and has continued to exert a major influence on Guam until the present. Chief Quipuha (Keupha) was the maga’lahi, or high ranking male, in the area of Hagatna when the Spanish landed off its shores in 1668. Chief Quipuha was depicted as having stood tall and robust. Quipuha welcomed the missionaries and allowed himself to be baptized by San Vitores as Juan Quipuha. Quipuha granted the lands on which the first Catholic Church on Guam, the Dulce Nombre de Maria (Sweet Name of Mary) Cathedral Basilica, was constructed in 1669. The original cathedral was destroyed during World War II and the present Cathedral, depicted here, was constructed on the original site in 1955.

As the maga’lahi, in the Chamorro matriarchal society, Quipuha had the authority to hand down important decisions made with the advise and consent of the maga’haga, the highest ranking woman in his clan. During the period of the original cathedral construction, land was owned by clans. Only women could ‘inherit’ land, suggesting that the maga’haga of his clan must have agreed, or at least acquiesced, to the decision to grant the land for the Church. Chief Quipuha died in 1669, but his legacy had a tremendous impact by allowing the Spanish to successfully establish a strong foothold and base on Guam for the Manila Galleon trade. His statue today stands in Chief Quipuha Park in present day Hagatna.

Clash of Two Cultures

The Spanish were received with a mixture of curiosity and suspicion. Padre Diego Luis de San Vitoreswas a Jesuit Pries who tried to carry out his mission in a peaceful manner while the Spanish military ruthlessly governed the local populace to protect their Galleon Routes. Mata’pang, The maga’låhi, Chief, of the village of Tomhom (modern day Tumon), initially accepted the Spanish, allowing himself to be baptized. In April of 1672, however, while Mata’pang was away, Padre San Vitores and his Filipino assistant baptized the chief’s daughter without his consent and were killed by Chief Mata’pang in response. It is likely that Mata’pang acted out of frustration from being subjugated to the harsh rule of a foreign Spanish King. Regardless of Mata’pang’s motive, the death of Padre San Vitores lead to all-out war that resulted in the near extinction of the Chamorro race.

During the course of the Spanish occupation of Guam, sources have estimated that by 1741, Chamorro casualties to the fighting and disease reduced the population from 200,000 to roughly 5,000, mostly women and children. After 1695 Chamorro’s were forced to settle in five villages: Hagatna, Agat, Umatac, Pago, and Fena, were monitored by the priests and military garrison, forced to attend Church daily and to learn Spanish language and customs. The Spaniards imported Spanish soldiers and Filipino’s to restock the population, marking the end of the pure Chamorro bloodline. In 1740, Chamorro’s of the Northern Mariana Islands, except Rota, were removed from their home islands and exiled to Guam. Mata’pang himself was killed in a final battle on the Island of Rota in 1680. Having been vilified for the incident that sparked the decimation of the pure Chamorro race, the name Mata’pang has evolved to mean, possibly unfairly, someone who foolishly resists progress.

The Spanish Treasure Galleons

During the 18th century, Guam was a regular layover destination on the Spanish treasure galleon route between the Philippines and Mexico to take-on supplies and provisions. The Spaniards established their capitol in what is now Hagatana and constructed a coastal road, the El Camio Real, in 1785 to transport supplies from Hagatna to Umatic. The San Antonio bridge in Hagatna and Talafak bridge in Agat are the original bridges constructed in 1785. The Galleon era ended in 1815 following the Mexican Revolution. Over the centuries, due to it’s strategic location, Guam has been host to voyagers, scientists and whalers from Germany, Russia, France and England, some of whom provided detailed accounts of the daily life on Guam under Spanish rule.

The Galleons were preyed upon by English pirates. The Spanish built a number of forts to protect their the Galleons and their colony on Guam. Fort Santa Ageuda, on the cliff line overlooking Hagatna and Hagatna Bay, protected the capitol from attacks from the sea. Forts Nuestra Senora de la Soledad and Fort Santo Angel protected the Umatic Bay. Forts Santa Agueda and Soleda still stand where they did in the 1700’s. All that remains of Fort Santo Angel are remants of some of the walls at the Northern entrance to the mouth of Umatic Bay.

Evidence of Spanish influence on Guam can still be seen across the island today. Early 18th Century Spanish buildings, bridges, churches and forts still stand across the island, especially in the Southern areas. Spanish cannon still overlook Hagatna and Umatac Bays from Forts Agueda and Soledad. The Plaza de Espana, once the Spanish Governor’s Palace, still stands in central Haganta. Sunken Spanish galleons still lie under Guam’s crystal clear waters. The architecture and design of structures built long after the Spanish era still have a distinctively Spanish quality.

| Ancient Guam through the Spanish Era |

* | US Territory and Japanese Occupation |

Welcome to Guam

Welcome to Guam The Beginning”

The Beginning” Latte Stone Park

Latte Stone Park Taotaomona

Taotaomona Umatic Bay

Umatic Bay Plaza de Espana

Plaza de Espana Dulce Nombre de Maria

Dulce Nombre de Maria Chief Quiphua Statue

Chief Quiphua Statue Padre Diego Luis

Padre Diego Luis Chif Mata’Pang

Chif Mata’Pang Tailafak Bridge

Tailafak Bridge Fort Santa Agueda

Fort Santa Agueda Fort Soledad

Fort Soledad